[ENGLISH VERSION]

Brazil’s economy

Desperate times, desperate moves

Beset by dismal economic data, Dilma Rousseff tosses Congress a challenge

WHEN a president has single-figure approval ratings, faces calls for

her impeachment, and has lost control of her political base, is she in a

position to play hardball with the country’s legislators? Brazilians

will soon find out.

On August 31st Dilma Rousseff, their president, sent Congress a

budget for 2016 with a gaping primary deficit (before interest payments)

of 30.5 billion reais ($8 billion), or 0.5% of GDP, challenging its

members to close the gap. It was a break with the sound-money practices

that have underpinned Brazil’s economy. It was, some critics say,

illegal. Certainly nothing similar has happened since at least 2000,

when Fernando Henrique Cardoso, then the president, transformed public

finances.

On a charitable view, Ms Rousseff was shocking legislators into

making hard decisions rather than simply blocking her fiscal proposals. A

harsher reading is that she does not know how to lead Brazil out of

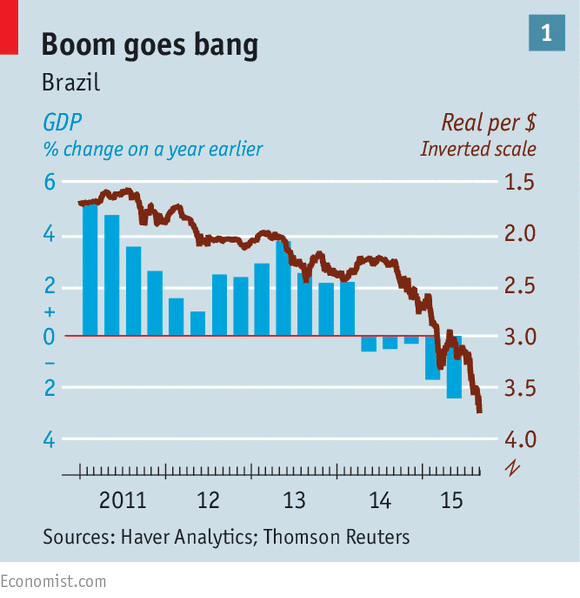

recession. The markets took that view. The day after the budget

bombshell, the Ibovespa stock index fell over 2% and the currency closed

at 3.7 per dollar, its lowest since December 2002. On September 2nd,

the central bank held steady a key interest rate it had been raising

since last year.

Public finances have already deteriorated this year. Having

originally planned a primary surplus of 1.1%, in July the government cut

that target to just 0.15%, as interest rates rose and tax receipts

fell. The total deficit this year will be 8-9% of GDP. In August

Moody’s, a rating agency, cut its assessment of Brazil by a notch to

just above junk status. It hinted at worse to come by calling the latest

news a sign of “the fiscal challenges that Brazil continues to face”.

The risk of a downgrade is one reason for the pessimism which, some

pundits think, is now the prevailing mood in the corridors of power.

“The government is basically throwing in the towel,” says Alberto Ramos,

an economist with Goldman Sachs, an investment bank.

Ms Rousseff is in a tight corner. She issued her budget after

scrapping a plan to reinstate a tax on financial transactions that would

have brought in 80 billion reais in 2016. She retreated after her

vice-president, Michel Temer, rejected the idea and told her Congress

would block it. Several opposition figures say that, far from finding a

way to make Congress do homework, the president has broken a

fiscal-responsibility law enacted in 2000 as part of an effort to mend

Brazil’s finances after decades of chaos. They say they may take her to

court.

On this point, the president may be right. Mansueto Almeida, an

economist who is critical of Ms Rousseff, says that though the law

requires the executive to show how its spending will be funded, it

allows a rise in debt. Júlio Marcelo de Oliveira, a prosecutor for the

Federal Court of Accounts, agreed that the president, whose alleged

budgetary misdeeds he has previously investigated, acted legally this

time.

Legal or not, the president’s move weakens her American-trained

finance minister, Joaquim Levy, who was reported to have lobbied for

further spending cuts and was a reassuring figure for markets. Ms

Rousseff has consistently failed to hit economic targets since being

elected in 2010, but in the early days she dodged the political flak.

Many people blamed her then finance minister, Guido Mantega, who was

known for over-promising. Replacing him with Mr Levy was supposed to fix

that problem; his loss of face bodes ill.

To restore credibility, Mr Ramos argues, the government needs to end

up with a primary surplus of 3.0-3.5% of GDP. Simply stabilising the

debt-to-GDP radio is not good enough, he says: it is already too high.

At a minimum, tough horse-trading with Congress looms. Renan Calheiros,

the president of Brazil’s Senate who has had several rows with Ms

Rousseff this year, said on September 1st he would not send the budget

back to her, as many opposition people want. “It is up to Congress to

improve it,” he accepted. And on any fair assessment, Congress shares a

lot of blame for Brazil’s economic woes; for example, it neutered many

of Mr Levy’s better ideas.

Is there any way out? It looks unlikely that tax rises can be

avoided: about 90% of the budget is ring-fenced, leaving little

discretion for spending cuts. If the government were strong and

confident, it might acknowledge the need for a short-term rise in debt

while seeking ways to limit spending on pensions, health and education,

and laying out a long-term plan to restore fiscal health. But pushing

such reforms through Congress would take political will and capital, and

this was not done during Brazil’s boom years when it would have been

easier. Now, says Mr Almeida, “We are paying for all of the mistakes

[of] the past five years.” The mystery, he adds, is why Brazil has not

lost its investment grade already.

Advertisement

China’s economy: How China’s cash injections add up to quantitative...

China’s economy: How China’s cash injections add up to quantitative...

Free exchange

The Economist explains: The decline of bees

The Economist explains: The decline of bees

The Economist explains

Migrants, Christianity and Europe: Diverse, desperate migrants have...

Migrants, Christianity and Europe: Diverse, desperate migrants have...

Erasmus

Saudi Arabia and America: King Salman visits the White House at last

Saudi Arabia and America: King Salman visits the White House at last

Middle East and Africa

The American economy: New jobs numbers do little to illuminate the Fed's...

The American economy: New jobs numbers do little to illuminate the Fed's...

Free exchange

Emerging economies: Turbulent markets in the suspect six

Emerging economies: Turbulent markets in the suspect six

Free exchange

Daily chart: A discussion with the Donald

Daily chart: A discussion with the Donald

Graphic detail

Advertisement

Products and events

Test your EQ

Take our weekly news quiz to stay on top of the headlines

Take our weekly news quiz to stay on top of the headlines

Want more from The Economist?

Visit The Economist e-store and you’ll find a range of carefully selected products for business and pleasure, Economist books and diaries, and much more

Visit The Economist e-store and you’ll find a range of carefully selected products for business and pleasure, Economist books and diaries, and much more

Advertisement

==//==

[PORTUGUESE VERSION]

'The Economist' dá destaque à crise brasileira

Revista inglesa não poupa críticas aos rumos da economia do país, com ênfase no orçamento deficitário

por Aline Macedo*

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário