#THE CHALLENGE OF SAFER CORRUPTION APPEAL TRIAL IN PORTO ALEGRE

• Brazil braces for corruption appeal that could make or break ex-president (from theguardian)

• #Condemn TRF4 (4th Region of Brazilian Federal Regional Court )/#condena trf4

porto alegre in favor of justice defense and prision of lula (From MBL)

• In the Surroundings of the TRF4 will have 'aerial, terrestrial and naval' blockade from Tuesday

SOURCE/LINK: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/23/brazil-luiz-inacio-lula-da-silva-corruption-appeal-verdict-election

Brazil

is bracing for a historic court decision which could remove the most

popular leader in modern Brazilian history from an election he is

currently poised to win – and may prove devastating to the leftwing

Workers’ party he founded.

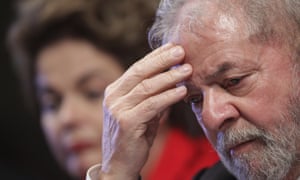

Nerves are stretched taut ahead of Wednesday’s appeals court

decision, in which three judges will decide whether or not to uphold the

conviction of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva on corruption and money laundering charges.

Lula

– who is still hugely popular after his 2003-2010 two-term presidency –

is currently the early favourite in October’s presidential election.

Porto Alegre’s rightwing mayor Nelson Marchezan asked for the army to

protect the city from thousands of Lula supporters expected to descend.

The Workers’ party president, Gleisi Hoffmann, said last week that for

Lula to be arrested, “they will have to kill people” – although she

later qualified the remark.

Authorities have closed airspace over the court, sealed off the

surrounding streets, and plan to deploy helicopters, elevated

observation platforms and even rooftop sharpshooters.

Lula’s many enemies are already planning victory celebrations in a park on the affluent side of the city, but his successor Dilma Rousseff

said upholding the conviction would stop Brazil reducing the brutal

inequality her party fought since first winning election in 2002.

“We are looking at the future of our country,” she told the Guardian

in an interview in Porto Alegre, where she now lives. “This is not a

short-term conflict.”

He was handed a nine-and-a-half-year sentence for corruption and money laundering in July by Sérgio Moro, a high-profile judge known for imposing tough sentences over a sprawling, multibillion-dollar graft case at state-run oil company Petrobras. Scores of powerful politicians and businessmen have been jailed as a result of the so-called Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigation.

Fury over the scheme, revealed in 2014, helped fuel massive street protests calling for the removal of Lula’s protege Rousseff – and also galvanised a resurgent Brazilian right.

Rousseff was eventually impeached in 2016, ostensibly for breaking budget rules, and was replaced by her former vice-president, Michel Temer, from the Brazilian Democratic Movement party (PMDB, since renamed MDB). Wiretaps later revealed PMDB politicians plotting to force Rousseff out in order to head off corruption investigations they themselves were implicated in.

Temer has since introduced severe austerity measures to combat public spending which had soared under Rousseff’s rule; poorer Brazilians have been hard hit by his cuts to social programmes.

Rousseff said the case against Lula, one of several, was part of the same conspiracy as her impeachment, which she described as a “coup” designed to dismantle the Workers’ party and introduce the market-friendly, “neo-liberal” agenda Temer is now pushing.

“We realised too late the rise of the extreme right within the PMDB. We had no notion,” Rousseff said.

She admitted her party had been involved in diverting some money, but said it was much less than others, like the PMDB. “Every party in this process had its deviations,” she said.

Lula was found guilty of receiving about £540,000 ($755,000) in bribes from a construction company called OAS in the form of a seaside duplex apartment renovated and swapped for a simpler apartment he had bought in the same building.

Prosecutors said the company paid nearly £20m in bribes for three fat Petrobras contracts.

Lula appealed, but the Porto Alegre court has upheld many of Moro’s sentences, and its president, Carlos Lenz, has praised his rulin .

Human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson QC said Moro had failed to prove a link between the apartment and a specific act or decision by Lula.

“Moro hasn’t found the smoking gun, because it does not exist,” Robertson said in a statement.

Lula’s lawyers say that Lula never owned the apartment and described the case as a “legal farce” in a statement.

Meanwhile, Brazilian leftists said losing Lula from the election would be a devastating blow for his Workers’ party.

“It would be a catastrophe,” said Jean Wyllys, a Rio de Janeiro lawmaker for the Socialist and Freedom party. “Our democracy is already in intensive care.”

Officially, the party has no “plan B” candidate, and Hoffmann told the Guardian they will push his candidacy right down to the wire.

But some party officials believe Lula’s growing popularity is enough to propel a last-minute substitute to victory if he ends up being removed from the race.

“He could. But sincerely, we made a deal not to talk about this,” said Jorge Branco, the party’s secretary for international relations for Rio Grande do Sul state.

Plenty of Brazilians blame Rousseff for a crippling recession Brazil has officially just emerged from and Lula for Brazil’s endemic culture of graft.

“Everything is connected to what they did to Petrobras,” said Mauro de Paiva, 53, a one-time Lula voter who lost his job at a Porto Alegre soccer team last year.

But conversely, Lula’s popularity has only risen in polls, with 49% saying they would vote for him over far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro in a run-off vote in one December poll.

“The more he is persecuted, the more his support grows,” said Branco.

Additional reporting by Sam Cowie.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are

reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media

are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up

a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you

can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent,

investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to

produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters –

because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information. Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as £1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

© 2018 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

•

==//==

VIDEO LINK: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgSU67nN-Ks

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=+%23CONDENATRF4

LINK: https://twitter.com/twitter/statuses/955930040960716802

#CONDEMN TRF4 (4TH REGION OF BRAZILIAN FEDERAL REGIONAL COURT )/#CONDENA TRF4

PORTO ALEGRE IN FAVOR OF JUSTICE DEFENSE AND PRISION OF LULA

#CONDENA TRF4

PORTO ALEGRE POR JUSTIÇA E LULA NA CADEIA

ATOS NA PAULISTA E EM PORTO ALEGRE

==//==

SOURCE / LINK: http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral-entorno-do-trf4-tera-block-aero-terrestre-en-naval-a-partir-de-terca-feira.70002160430

In the Surroundings of the TRF4 will have 'aerial, terrestrial and naval' blockade from Tuesday

Surveillance will have snipers on top of buildings watching, shooting and filming protesters

Taís Seibt, from Porto Alegre, O Estado de S.Paulo

22 January 2018 | 13:02

PORTO ALEGRE - Access to the environment of the Regional Federal Court of the 4th Region (TRF-4) will be restricted from 12h on Tuesday, the 23rd day before the trial of the appeal of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in the case of the Guarujá triplex. The restriction in the perimeter will be by "air, land and naval", according to the Secretary of Public Security of Rio Grande do Sul, Cezar Schirmer.

Lula has stated that he will continue to 'fight' until the end to compete in the October election. Photo: Nilton Fukuda / Estadão

Clarifications regarding the security scheme involving dozens of state, state, and federal agencies were provided to the press on the morning of Monday, 22. Schirmer, however, avoided any details regarding the costs and size of operation, saying only that the integrated security forces will have the "necessary force" to guarantee the manifestation "within the constitutional principles".

+++ Stories of the Class of the TRF-4 that will judge Lula

Privacy Policy

Receive quality content in your email

Sign

Aircraft will monitor airspace and security forces vessels are already being positioned on the Guaíba Waterfront, close to the court, to avoid any access to the restricted area. There is also the possibility of using aircraft to transport judges to the court, if there is a risk or impediment to road transport.

By land, the restriction to the perimeter of the TRF-4 will be demarcated by means of gradis, besides the presence of police force. There will be only one access to the premises, for people previously registered by the court. The blockade of the area will affect the expedient of public agencies, which will be closed from 12 noon on Tuesday, and about 20 bus lines will have a detour route from midnight on Wednesday. Already on Tuesday afternoon, 23, the circulation of even pedestrians will be controlled on the spot, with no set time for unblocking.

"The perimeter will be isolated for as long as it takes to ensure order and safety for TRF4," said Brigadier General Andreis Dell Lago.

In addition to the surroundings of the TRF-4, also the Avenida da Legalidade, in the access to the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, will have traffic diverted from 5 am on Wednesday morning, the day of the trial. Other points of interest for demonstrations both favorable and contrary to former President Lula will also be monitored.

"We will be prepared to identify anyone who wants to make any manifestations that contradict legislation, including masquerading," emphasized Schirmer, stressing the agreements reached with social movements in the sense of cooperation and possible accountability in case of acts of violence or depredation.

The actions in support of Lula will be concentrated in the Sunset Amphitheater, a few blocks from the TRF-4, and in the "democratic corner" in the center of Porto Alegre. Already the demonstrations against the former president are being called to the Moinhos de Vento Park, the Parcão.

Three hundred journalists in Lula's trial

SHOOTERS

Schirmer says snipers will be on top of buildings around the perimeter as observers, filming and photographing demonstrators.

"The presence of snipers is part of any prevention process. Sniper is actually an observer. It will shoot last case in a most expancional condition. He is an observer of physical space of what is happening. It will stay in the higher parts. Let's change the expression by privileged observer, including photographing and filming, "said the Secretary of Security.

Related news

• Outdoors in Porto Alegre ask for 'Lula in jail'

More content about:

TRF [Federal Regional Court] Lula [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] Guarujá [SP]

Have you found an error? Contact

Follow the Estadão

Institutional

• Code of ethics

• Anti-corruption policy

• Journalism course

• Accounting statements

• Terms of use

Attendance

• Corrections

• Subscriber Portal

• Contact us

• Work with us

Contact Us |

• Broadcast

• Political Broadcast

• Applications

DIGITAL EDITION

• Collection

• SME

• Car Journal

• Palate

• Link

ILocal

• State Agency

• Eldorado Radio

Home

• Moving Real Estate

Copyright

==//==

SOURCE/LINK: http://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,entorno-do-trf4-tera-bloqueio-aereo-terrestre-e-naval-a-partir-de-terca-feira,70002160430

Entorno do TRF4 terá bloqueio ‘aéreo, terrestre e naval’ a partir de terça-feira

Vigilância terá atiradores de elite no topo dos edifícios observando, fotografando e filmando os manifestantes

0

•

Taís Seibt, de Porto Alegre, O Estado de S.Paulo

22 Janeiro 2018 | 13h02

PORTO ALEGRE - O acesso ao entorno do Tribunal Regional Federal da 4.ª Região (TRF-4) ficará restrito a partir das 12h desta terça-feira, 23, véspera do julgamento do recurso do ex-presidente Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva no caso do triplex do Guarujá. A restrição no perímetro será por via “aérea, terrestre e naval”, segundo o secretário de Segurança Pública do Rio Grande do Sul, Cezar Schirmer.

Lula declarou que vai continuar 'brigando' até o final para concorrer no pleito de outubro. Foto: Nilton Fukuda/Estadão

Os esclarecimentos em relação ao esquema de segurança, que envolve dezenas de órgãos municipais, estaduais e federais, foram prestados à imprensa na manhã desta segunda, 22. Schirmer, no entanto, evitou qualquer detalhamento em relação aos custos e ao tamanho do efetivo envolvido na operação, dizendo apenas que as forças de segurança integradas terão o “efetivo necessário” para garantir a manifestação “dentro dos princípios constitucionais”.

+++ Histórias da Turma do TRF-4 que vai julgar Lula

Newsletter Política

Receba no seu e-mail conteúdo de qualidade

Assinar

Aeronaves farão o monitoramento do espaço aéreo e embarcações das forças de segurança já estão sendo posicionadas na Orla do Guaíba, nas imediações do tribunal, para evitar qualquer tipo de acesso à zona restrita. Há, inclusive, a possibilidade de se utilizar aeronaves para o transporte dos desembargadores até o tribunal, caso haja risco ou impedimento para o transporte rodoviário.

Por via terrestre, a restrição ao perímetro do TRF-4 será demarcada por meio de gradis, além da presença de efetivo policial. Haverá apenas um acesso ao local, para pessoas previamente cadastradas pelo tribunal. O bloqueio da área afetará o expediente de órgãos públicos, que ficarão fechados a partir das 12h de terça, e cerca de 20 linhas de ônibus terão rota desviada a partir da meia-noite de quarta. Já na tarde de terça-feira, 23, a circulação até mesmo de pedestres será controlada no local, sem horário definido para desbloqueio.

“O perímetro ficará isolado o tempo necessário para garantirmos a ordem e a segurança ao TRF4”, disse o comandante-geral da Brigada Militar, Andreis Dell Lago.

Além do entorno do TRF-4, também a Avenida da Legalidade, no acesso à capital gaúcha, terá o trânsito desviado a partir das 5h da manhã de quarta-feira, dia do julgamento. Outros pontos de interesse para manifestações tanto favoráveis quanto contrárias ao ex-presidente Lula também serão monitorados.

“Nós vamos estar preparados para identificar quem queira fazer qualquer manifestação que contrarie a legislação, inclusive mascarados”, enfatizou Schirmer, destacando os acordos estabelecidos com movimentos sociais no sentido de cooperação e eventual responsabilização em caso de atos de violência ou depredação.

As ações em apoio a Lula ficarão concentradas no Anfiteatro Pôr-do-Sol, a poucas quadras do TRF-4, e na “esquina democrática”, no centro de Porto Alegre. Já as manifestações contrárias ao ex-presidente estão sendo convocadas para o Parque Moinhos de Vento, o Parcão.

+++ Trezentos jornalistas no julgamento de Lula

ATIRADORES

Schirmer afirma que atiradores de elite vão ficar no topo de edifícios próximos ao perímetro com a função de observadores, filmando e fotografando os manifestantes.

“A presença de atiradores de elite faz parte de qualquer processo de prevenção. Atirador de elite é na verdade um observador. Vai atirar em último caso numa condição expepcionalíssima. Ele é observador de espaço físico do que está acontecendo. Vai ficar nas partes mais altas. Vamos trocar a expressão por observador privilegiado, inclusive fotografando e filmando”, afirmou o secretário de Segurança.

Notícias relacionadas

• Outdoors em Porto Alegre pedem ‘Lula na cadeia’

Mais conteúdo sobre:

TRF [Tribunal Regional Federal] Lula [Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] Guarujá [SP]

Encontrou algum erro? Entre em contato

Siga o Estadão

•

•

THE END

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário